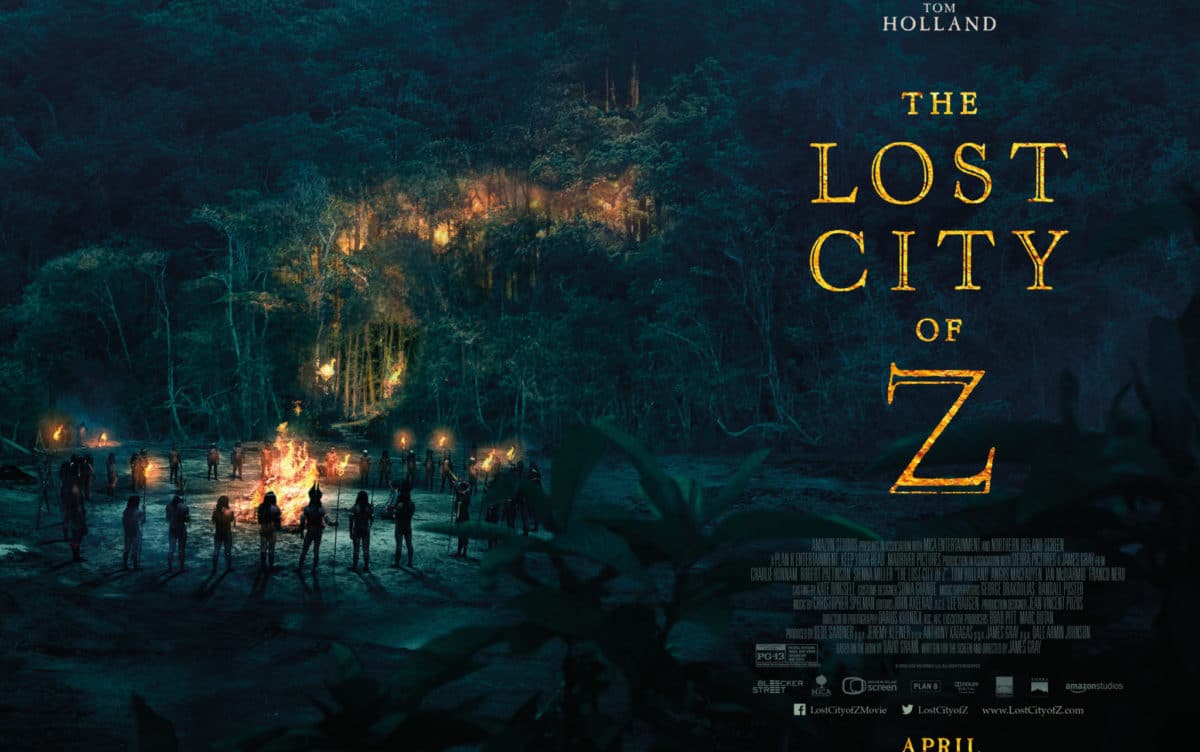

Review: The Lost City of Z (2017)

The story of explorers becoming transfixed by the wonders (and rubber industry) of the Amazon has almost become its own sub-genre at this point. With the likes of Fitzcarraldo, Embrace of the Serpent, and Aguirre, the Wrath of God, it also contains some of the most brilliantly realized films in cinematic history. Sure, that might be primarily because they’re Werner Herzog’s bread and butter, but that’s neither here nor there — let’s talk Lost City of Z!

Starting in 1906, we follow British colonel and cartographer Percival Fawcett (Charlie Hunnam) as he is sent to the Amazon jungle to map out and find the source of the Rio Verde. Joined by partner Henry Costin (Robert Pattinson), Percy succeeds in the venture, but in the process discovers evidence of civilization then unknown to archaeologists. An adventurous man ahead of his time, Percy sets forth to discover what he dubs “Z”, a lost civilization deep within the Amazon jungle. In doing so, he earns the wrath of his contemporaries and contends with long absences from his wife Nina (Sienna Miller) and children, earning especially harsh criticism from son Jack (Tom Holland). As the Great War approaches and each of his trips to South America become more perilous and fraught with problems, Percy must also deal with the possibility that he may never fulfill his dreams.

Clocking in at just under 2 1/2 hours, The Lost City of Z is right at home with its predecessors in giving plenty of screen time to its exotic subject matter. What makes this film different from those is that a hefty amount of its script is spent on Percy’s home life and dealing with the blowhards and ignorant mindsets at the Royal Geographic Society, which funds his initial expeditions. Whether it’s the old school Sir George Goldie (Ian McDiarmid) or the initially supportive and rotund James Murray (Angus Macfadyen), these British aristocrats tend to be even worse hinderances than the dangers of the jungle. Percy, being the misunderstood hero that he is, actually feels more at home and perhaps even safer in the Amazon. His only solace back home comes in the form of his family, whom he shows incredible compassion, but nonetheless shirks in favor of his green desert.

One of the few real problems with director James Gray’s adaptation of David Grann’s bestselling book is that it only has so much time to work with so much story. Even after cutting down the true story’s seven expeditions and adding character amalgamations to keep things moving along, there is a feeling that this might have worked better as an HBO or Netflix miniseries. Trapped in its current runtime, the movie struggles to do justice to all of the characters and even some of the expeditions.

In Percy’s fateful final journey, the jungle feels small. While Gray manages to combine the explorer’s two greatest loves and works to satisfactorily conclude the true story with just a bit of whimsy, the narrative is forced into overdrive to make up for all of the time spent building up to this point. That doesn’t necessarily hurt the film significantly, but the idea of a six-hour television version does creep up like an Apazauca spider from time to time, reminding you of its potential.

Director of photography Darius Khondji (Amour, The City of Lost Children), who has shot some of the most perfectly realized films of the last three decades, continues his recent trend of being deliberately understated. Shots meander in and out of focus with a wide open aperture and grainy film stock (Lost City of Z was shot on a mix of digital and 35mm Kodak Vision3). and the warmth and dirtiness of the jungle stands in sharp contrast to the cold, foggy look of England. Styles mix together for home life and our short time on the front lines, expertly framing our perceptions through Percy’s own.

Charlie Hunnam, often derided as another bland foreign leading man alongside the likes of Jai Courtney and Sam Worthington, shows off the skills viewers of Sons of Anarchy have enjoyed for years. Presenting Percy with a calm and masculine presence and utilizing every ounce of Britishness he can muster, Hunnam shows that he’s more than just a pretty face. Through his performance, the audience feels compelled to go on these arduous journeys with him, and to sigh with frustration as his quest for truth is set back time and time again by forces beyond his control. He nails the part, and hopefully this role leads to much more Hunnam in our cinematic diet.

Speaking of British actors often derided as bland, let’s take a moment to appreciate Robert Pattinson’s career path. Not only is he nigh unrecognizable here, but he comes off as a legitimate human being. As Henry Costin, Percy’s righthand man (in the movie, anyway), he is endlessly reliable. Even when on the verge of death from hunger and disease, Costin manages to shoot a mutineering member of their crew before he can slice up our hero. His dedication, as well as ability to go from drunken reprobate to skin-and-bones adventurer to 1920s British everyman, is one of the little treasures hidden in Lost City. It feels like a million years since Pattinson dawned his most famous glitter-glow persona for millions of screaming fangirls, and that’s all too refreshing for those of us waiting for him to continue the career path begun in How To Be and Little Ashes.

The rest of the cast are equally deserving of paragraphs full of praise, but I’m not cruel enough to put you through that. Sienna Miller is even more unrecognizable than Pattinson, and it seems like the film would have benefited from more of her perspective. Tom Holland only really becomes a major player in the third act, but his brief turn as Percy’s son is both appreciated and pivotal. Franco Nero makes a very brief cameo as a rubber baron when Percy first arrives in the Amazon, and while it’s little more than a throwaway reminder of ’70s filmmaking (no doubt his role would have gone to Klaus Kinski if that madman were still alive), it’s a welcome detour into nostalgia.

To call The Lost City of Z equal to the tales of madness presented to us by Herzog would be inaccurate, but it’s also an unfair comparison. While Herzog played fast and loose with facts in favor of experimentation, crazy feats of production, and probably a need to survive the shoot, James Gray has made a film that attempts to tell the true story of a man who must choose between dreams and family. The cold nihilism brimming at the rim of Herzog’s Amazonian adventures is gone, in favor of a brash optimism that perfectly captures the real life character at its center. With this approach comes plenty of pitfalls, but I’m happy to say that it definitely survives the journey.