Review: Ghost in the Shell (2017)

After what seems like decades of back and forth about whether there would ever be a live action Ghost in the Shell film and who could possibly direct it, here we are at long last with Rupert Sanders’ American adaptation. Does it bring the cybernetic wizardry and heady pathos of the original manga and landmark 1995 animated film to the big screen? In a word . . . no.

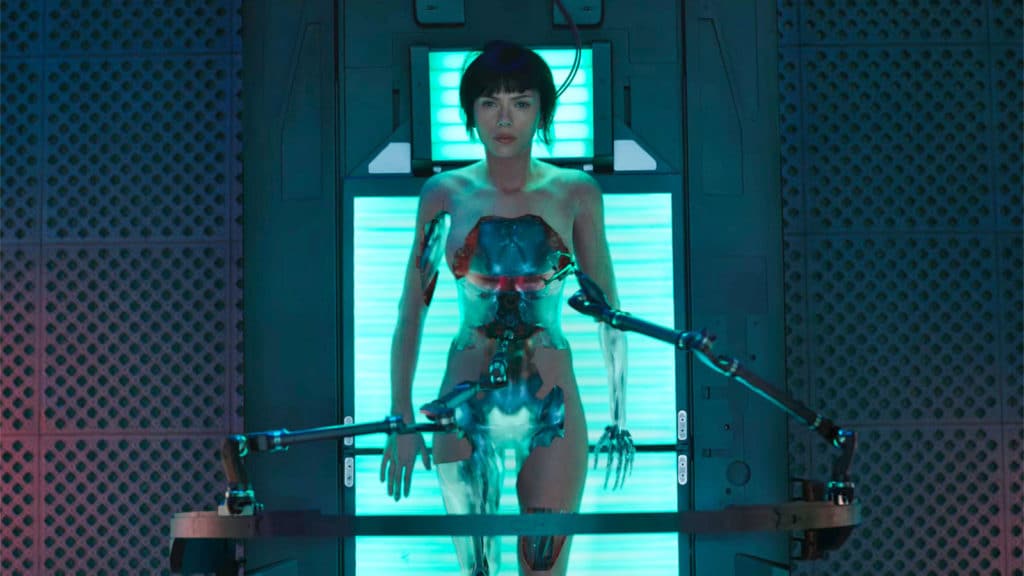

Centering around mysterious cyborg Major (Scarlett Johansson) and her fellow Department of Defense agents within Section 9, the plot follows her investigation into a mysterious cyberterrorist called Kuze (Michael Pitt). During the search, she experiences audiovisual glitches in her programming that lead her to believe her past may not be at all what she thought it was. This leads to a confrontation with the very company that built her.

As you could probably surmise from that synopsis or just the trailers themselves, 2017’s Ghost in the Shell is not a particularly complex film. Its characters are rarely given anything of substance to work with if they aren’t played by ScarJo, and the journey that she goes on is derivative to the point of parody. Rather than adapt the manga slightly more faithfully, we are instead invited into a world of familiar tropes that, if excised, would not have effected Ghost‘s better moments in the slightest.

One of those better moments, oddly enough, is a revelation that directly relates to the hostile reactions to Johansson being cast as the Major, who many had viewed as a character of Asian descent. It’s not going to quell their view that her casting was somehow racially motivated, or those who believe it is cultural appropriation to have her in the role, but then again those are mostly people who had already made up their mind about the filmmakers’ intent. While there’s no doubt casting a prominent white actress was a marketing maneuver (and one that failed, if this past weekend’s box office is any indication), the attempt at working it into the story was much appreciated. It’s too bad that the whole film couldn’t have spent more time on this philosophical quandary and less on corporate conspiracies.

On the more positive side of things, Sanders has put together a visually interesting film, full of holograms and little details that make the world feel more fleshed out than it really is. As Major and her partner Batou (Pilou Asbæk) walk through packed city streets, we’re treated to men with literal bubbles of tech around their heads and street cops with the word “POLICE” flashing in red and blue across their backs. In the seedier moments, we get a man with a slapdash cybernetic jaw and a badass bartender covered in equal parts tattoos and robotics. It’s a cool world that, while not as gritty as it probably wants to be, is nonetheless a sandbox I would have happily revisited in a sequel, preferably with a plot that allows more investigation and less boring introspection.

The cast is mostly sufficient, leaning toward good. Johansson makes the most of clunky dialogue and is reliably engaging, at least until the big “twist” comes around. Asbæk puts on a sincere veneer that only cracks when his Dutch accent slips out. Beat Takeshi is badass, though underused, while most of the rest of Section 9 are reduced to glorified cameos and never amount to the team we got in the source material. Veteran French actress Juliette Binoche shows up as Major’s creator, Dr. Ouelet, and gives the role all of the maternal care that it requires.

On the villainous side of things, we have Michael Pitt (who’s now using middle name Carmen in the credits, for whatever reason) and Cutter, played by Peter Ferdinando. If you like Michael Pitt, you’re going to keep doing so, because he makes for a creepy and sympathetic baddie. Ferdinando, on the other hand, is about as bland as humanly possible. which is astounding for an actor who held his own in films like A Field in England and Starred Up. The fact that he’s the big bad is disconcerting, and only adds to the feeling of blandness that stays with Ghost in the Shell. Perhaps a more engaged baddie performance would have kept audience interest between scenes of Major pontificating about her past and making questionable decisions, although that might be a stretch considering just how much screen time is dedicated to those bland elements.

That blandness is the nail in the coffin for what should have been a memorable film. The only notable imagery, aside from those creepy geishas and possibly Kuze’s underground base, comes directly from the 1995 anime, and it feels shoehorned in every time. Beyond those attempts at homage, a hefty chunk of the movie meanders through chaotic action and obsessive shots of a world that isn’t quite as revolutionary as Sanders seems to think it is. If he had taken the time to really self-criticize, he may have noticed that most of the themes, tone, and even music just come off as a less interesting version of what Blade Runner accomplished back in ’82. Considering the biggest criticism of the Ghost in the Shell franchise is its ample pilfering of that film, perhaps going with a more unique plot would have been advantageous.

One day, in a far future where the US is no more and Asian cultures have swirled together in the grimy drain of society, maybe, just maybe we’ll get a proper live action Ghost in the Shell; but by the time the credits roll and that sweet Kenji Kawai music finally springs up, this Ghost is all just an empty shell.